Pointers and Polymorphism

Polymorphism in C++ lets objects of different derived types be accessed through a common base class. While references can be used for polymorphism, pointers are essential when working with collections. Without pointers, polymorphic collections are subject to “object slicing” where only the base part of an object is stored, with the derived behavior “sliced” off.

Table of Contents

- Polymorphism in C++

- An Example Hierarchy

- Our Class Diagram

- The Polymorphism We Want

- Naive Incorrect Implementation of Polymorphism

- Virtual Functions to the Rescue

- Working Implementation of Polymorphism

- Virtual Destructors

- Polymorphism and Containers

- Example of a Polymorphic Container

Polymorphism in C++

Some quick OO terms to remember from our classes module:

- Base Class - A class that other classes inherit from. (Often called a parent class in other languages.)

- Derived class - A class that inherits from a base class. (Often called a child class in other languages.)

- Derived classes share an interface inherited from their common base class.

- Subtype Polymorphism - The ability to use the shared interface of derived classes by way of references or pointers to the base class.

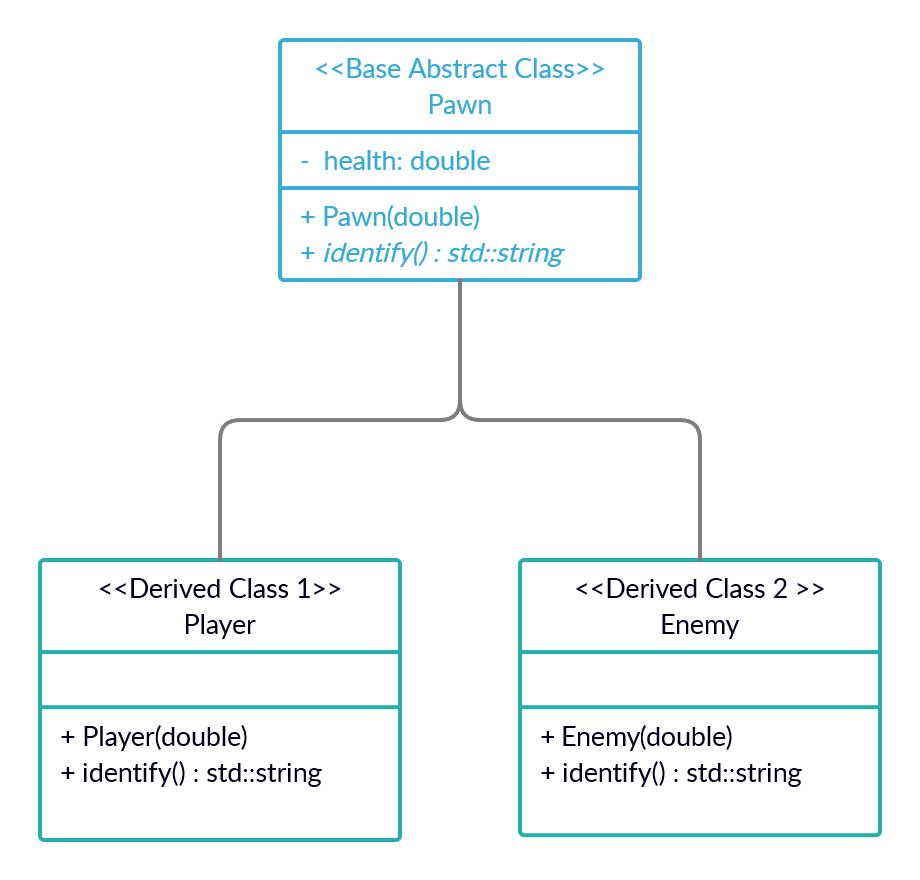

An Example Hierarchy

Imagine the following simple class hierarchy:

- An abstract base class

Pawn:- One

healthmember of typedouble. - Simple constructor.

- Function

std::string identify().

- One

- Derived class

Player:- Simple constructor that makes use of parent constructor.

- Overrides

std::string identify().

- Derived class

Enemy:- Simple constructor that makes use of parent constructor.

- Overrides

std::string identify().

Our Class Diagram

The Polymorphism We Want

The code below shows what we want to be able to do.

Notice that we trigger the polymorphism by way of two overloaded printPawnId functions. There’s one version that takes a reference to a Pawn and another that takes a pointer to a Pawn.

The overloaded functions aren’t both required. We’ve implemented both to demonstrate polymorphism via references and pointers.

// Accepts Player or Enemy References:

void printPawnId(const Pawn& p) {

std::cout << "REF - " << p.identify() << "\n";

}

// Accepts pointers to Player or Enemy object:

void printPawnId(const Pawn* p) {

std::cout << "PTR - " << p->identify() << "\n";

}

// Elsewhere in the code:

Player wally{ 90.0 };

Enemy daisy{ 100.0 };

printPawnId(wally); // Prints: REF - Player here!

printPawnId(daisy); // Prints: REF - Enemy here!

printPawnId(&wally); // Prints: PTR - Player here!

printPawnId(&daisy); // Prints: PTR - Enemy here!

Naive Incorrect Implementation of Polymorphism

Here’s a naive and broken implementation of polymorphism for the Pawn, Player and Enemy class. Notice that when we try to polymorphically call a Player’s or Enemy’s identify() method, the Pawn implementation is used instead.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

class Pawn {

double health;

public:

Pawn(double health) : health{health} {

std::cout << "Pawn Constructor\n";

}

std::string identify() const {

return "Pawn here!";

}

};

class Player : public Pawn {

public:

Player(double health) : Pawn(health) {

std::cout << "Player Constructor\n";

};

std::string identify() const {

return "Player here!";

}

};

class Enemy : public Pawn {

public:

Enemy(double health) : Pawn(health) {

std::cout << "Enemy Constructor\n";

};

std::string identify() const {

return "Enemy here!";

}

};

// Polymorphically call identify() on references to Pawn

// objects. Can also be passed Player or Enemy objects.

void printPawnId(const Pawn& p) {

std::cout << p.identify() << "\n";

}

// Polymorphically call identify() via pointers to Pawn

// objects. Can also be passed Player or Enemy pointers.

void printPawnId(const Pawn* p) {

std::cout << p->identify() << "\n";

}

int main() {

std::cout << "Constructing a Player: \n";

Player wally{ 90.0 };

std::cout << "\nConstructing an Enemy: \n";

Enemy daisy{ 100.0 };

std::cout << "\nPrinting Pawn Ids by Reference: \n";

printPawnId(wally); // Oh No! Prints: Pawn here!

printPawnId(daisy); // Oh No! Prints: Pawn here!

std::cout << "\nPrinting Pawn Ids by Pointer: \n";

printPawnId(&wally); // Oh No! Prints: Pawn here!

printPawnId(&daisy); // Oh No! Prints: Pawn here!

}

Virtual Functions to the Rescue

A virtual function is a special kind of class member function that, when called, executes the most-derived version of that function. For our example code above to work, we will need to make identify() a virtual function in the base Pawn class. Although not required, we will mark the identify() implementations in the derived classes as overrides using the override keyword.

If it doesn’t make sense to implement a virtual function in the base class, we can mark it as a “pure virtual function”. A pure virtual function is a function declared in a base class with = 0, meaning it has no implementation. Any class with at least one pure virtual function is considered ‘abstract’ and cannot be instantiated. Abstract classes are used to define common interfaces that derived classes must implement.

We’ll make the Pawn class abstract in this way.

💡 Best Practice:

Make base class destructors virtual so that derived destructors can be used.

Working Implementation of Polymorphism

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

// Abstract Base Class Pawn

class Pawn {

double health;

public:

Pawn(double health) : health{health} {

std::cout << "Pawn Constructor\n";

}

// Virtual destructor in case we ever want derived destructors.

virtual ~Pawn() = default;

// Pure virtual identify() with no function body.

virtual std::string identify() const = 0;

};

// Derived Class Player

class Player : public Pawn {

public:

Player(double health) : Pawn(health) {

std::cout << "Player Constructor\n";

};

std::string identify() const override {

return "Player here!";

}

};

// Derived Class Enemy

class Enemy : public Pawn {

public:

Enemy(double health) : Pawn(health) {

std::cout << "Enemy Constructor\n";

};

std::string identify() const override {

return "Enemy here!";

}

};

// Polymorphically call identify() on references to Pawn objects.

void printPawnId(const Pawn& p) {

std::cout << p.identify() << "\n";

}

// Polymorphically call identify() via pointers to Pawn objects.

void printPawnId(const Pawn* p) {

std::cout << p->identify() << "\n";

}

int main() {

std::cout << "Constructing a Player: \n";

Player wally{ 90.0 };

std::cout << "\nConstructing an Enemy: \n";

Enemy daisy{ 100.0 };

std::cout << "\nPrinting Pawn Ids by Reference: \n";

printPawnId(wally);

printPawnId(daisy);

std::cout << "\nPrinting Pawn Ids by Pointer: \n";

printPawnId(&wally);

printPawnId(&daisy);

}

Virtual Destructors

When dealing with polymorphism, making the base class destructor virtual ensures that the destructor of the derived class is called when deleting an object through a base class pointer.

Failing to make your base class destructors virutal can lead to memory leaks or undefined behavior.

Polymorphism and Containers

Although polymorphism can be implemented using references, if we also wish to involve containers we need to use pointers.

In C++, containers can’t hold references directly because references do not have an assignable address. Therefore, when we want to store polymorphic objects in containers, we need to use pointers. This allows us to store and manage objects of varying types derived from a common base class.

Using pointers for polymorphism in containers allows us to store objects of different derived types without worrying about object slicing (which would happen if we stored objects by value). The dynamic memory allocation ensures that the full object, including its derived type-specific data and behavior, is preserved.

Example of a Polymorphic Container

Here’s an example of polymorphism using a vector of unique pointers:

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <memory>

#include <ctime>

// Abstract Base Class Pawn

class Pawn {

double health;

public:

Pawn(double health) : health{health} {

}

// Virtual destructor in case we ever want derived destructors.

virtual ~Pawn() = default;

// Pure virtual identify() with no function body.

virtual std::string identify() const = 0;

std::string healthReport() const {

return "Health: " + std::to_string(health);

}

};

// Derived Class Player

class Player : public Pawn {

public:

Player(double health) : Pawn(health) {

};

std::string identify() const override {

return "Player here! " + healthReport();

}

};

// Derived Class Pawn

class Enemy : public Pawn {

public:

Enemy(double health) : Pawn(health) {

};

std::string identify() const override {

return "Enemy here! " + healthReport();

}

};

// Polymorphically call identify() on references to unique Pawn pointers.

// Reference must be used as we can't copy unique pointers.

void printPawnId(const std::unique_ptr<Pawn>& p) {

std::cout << p->identify() << "\n";

}

int main() {

srand(time(nullptr));

// Vector of unique pointers to the base Pawn class.

std::vector<std::unique_ptr<Pawn>> pawns;

// Randomly add pointers to new Player or Enemy objects.

for(int i = 0; i < 10; ++i) {

if (rand() > (RAND_MAX / 2)) {

pawns.emplace_back(std::make_unique<Player>(50 + rand() % 50));

} else {

pawns.emplace_back(std::make_unique<Enemy>(50 + rand() % 50));

}

}

// Ranged-for must use a reference since we can't copy unique pointers.

for(const auto& pawn : pawns) {

printPawnId(pawn);

}

}