Trigonometry

Trigonometry is the mathematics of right-angle triangles and circles. We can use trig to simulate angular motion and waves. It can also be used to convert between different coordinate systems.

Table of Contents

- Objectives

- Textbook Chapter

- Oscillation

- Circular Logic

- Angles (Degrees)

- Why 360 Degrees?

- Angles (Radians)

- Radians Related to Radius

- A Slice of π

- But What is PI?

- Why Radians

- Processing Angles

- Angular Motion

- Angular Acceleration and Velocity

- Spin It!

- Noisy Rotation

- Trigonometry

- The Right Triangle

- Which Side Are You On?

- SOH CAH TOA - Right Triangle Sides and Angles

- The Triangle and The Circle

- Trig and The Circle

- Visualizing The Trigonometry of Circles and Right Triangles

- Resources

- Polar vs Cartesian Coordinates

- Polar and Cartesian Processing

- Why Polar Coordinates?

- From Vector to Heading

- Sprite Mouse Seekers

- Rotating Towards Movement

- A Minor Issue

- Let’s Surf

- Like Day and Night

- Waves with Amplitude and Period

- Angular Velocity in 2D

- Do the Worm

Objectives

By the end of this module you should be able to:

- Differentiate between radians and degrees for the measurement of angles.

- Use trigonometric functions to determine the missing lengths / angles of a right angle triangle.

- Differentiate between polar and cartesian coordinates.

- Use sin and cos to convert between polar and cartesian coordinates.

- Draw waves of varying complexity using sin within a p5js sketch.

Textbook Chapter

Chapter 3 - Oscillation - Nature of Code

Oscillation

In physics, oscillation is defined as regular variation in magnitude or position around a central point.

Understanding oscillation will allow us to simulate physical systems such as:

- The swing of a pendulum.

- The motion of a wave.

- The bounce of a spring.

- The orbit of a planet.

- The vibration of a guitar string.

But before we can get to oscillation, we need to review the mathematics of trigonometry.

Circular Logic

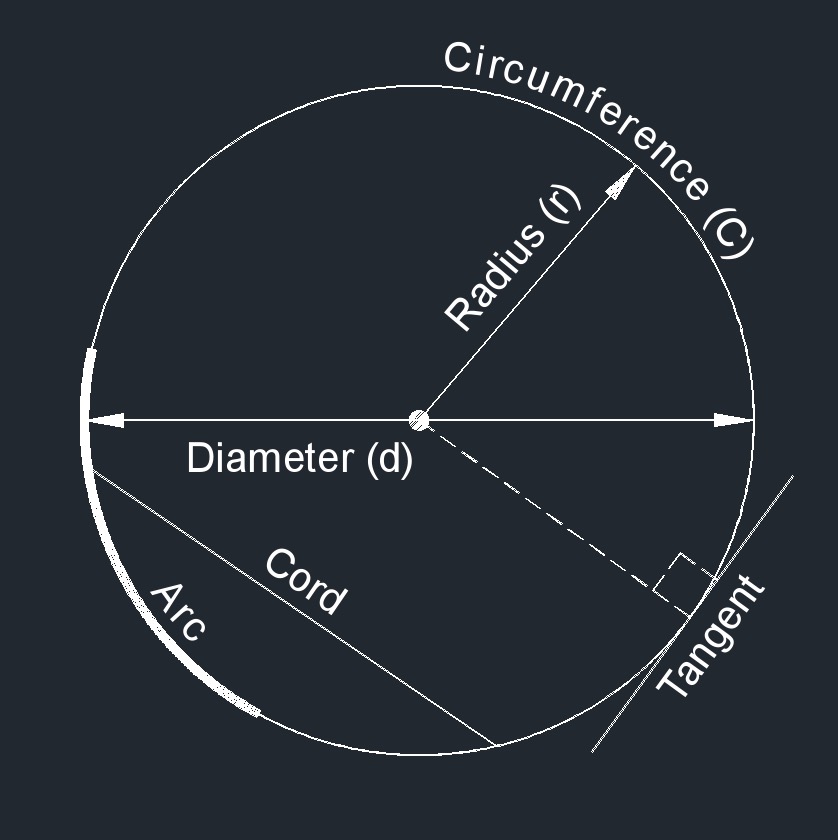

When talking about systems that involve a central point, we’ll undoubtedly reference circles, so let’s start there.

From Simple English Wikipedia:

A circle is a round, two-dimensional shape. All points on the edge of the circle are the same distance from the center.

The radius of a circle is a line from the centre of the circle to a point on the side. We’ll often use the letter r for the length of a circle’s radius.

A chord is a line segment whose endpoints lie on the circle.

The diameter of a circle is the chord that goes through the centre of the circle. We’ll use the letter d for the length of this line.

The circumference of a circle is the line that goes around the centre of the circle. We’ll use the letter C for the length of this line, and we’ll call a portion of the circumference an arc.

A tangent is a line that only shares a single point with a circle. Tangent lines are perpendicular (form a 90° angle with) a circle’s radius.

Angles (Degrees)

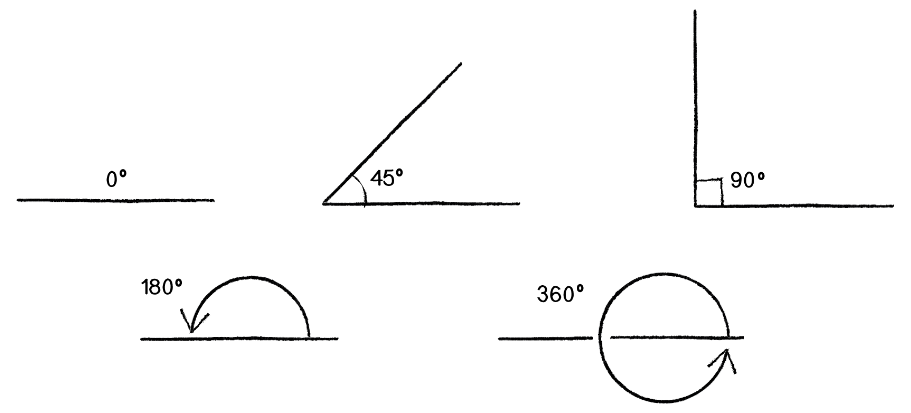

Circular rotation can be measured using an angle that can range from 0 to 360 degrees.

A quarter rotation is 90 degrees, and is said to be a right angle. A half rotation is 180 degrees and a full rotation is 360 degrees.

We use the ° symbol to indicate that a value is measured in degrees. Example: A right angle is 90°.

Why 360 Degrees?

The number 360 is arbitrary; we can segment a circle into as many arcs as we wish. The gradian unit, for example, divides a circle into 400 equal gons.

A theory on why there are 360 degrees:

- Humans noticed that star constellations moved in a full circle every year.

- Every day, they were off by a tiny bit (“a degree”).

- Since a year has about 360 days, a circle had 360 degrees.

360 is a nicer to work with number than 365.242199, the actual numbers of days in a year, especially since it has many whole number divisors.

A few of 360’s 20+ divisors: 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 45, 60, 90, 120, 180.

Angles (Radians)

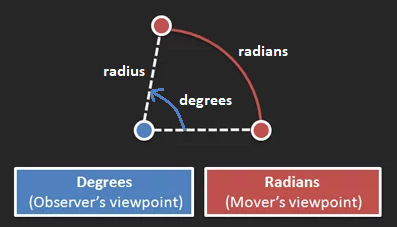

Degrees measure segments of a circle from an observer’s point of view as degrees of rotation, but there are other ways to measure these segments.

Imagine standing in the middle of a circular track watching a runner.

As the observer, you can measure the runner’s movement by how far (in degrees) you turned your head to watch the run, but this measurement means little to the runner. From their point of view, they’ve run a particular distance.

This is the basis for Radians, which reframes rotation as distanced traveled around a circle.

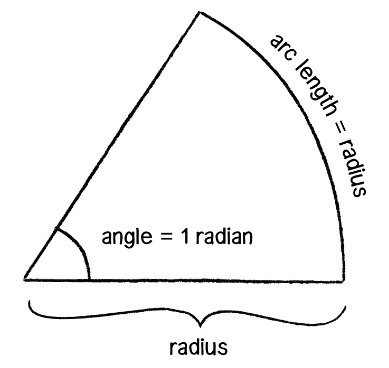

Radians Related to Radius

The distance of an arc around a circle depends on the size of the circle, so radians are measured in terms of a circle’s radius.

Specifically a radian is the ratio of a circle’s arc to its radius. 1 radian is the angle at which this ratio equals 1.

In other words, a rotation of 1 radian occurs when the distance traveled around a circle is equal to its radius.

Angles measured in radians are said to be rads. For example: 180° = π rads

A Slice of π

This is where pi (π) comes into the picture.

Pi is an irrational number with the approximate value of 3.1415926535...

Pi is baked into radian measurements:

- A full circular rotation (360 degres) is 2 * π radians.

- A half circle (180 degrees) is π radians.

- A quarter circle (90 degrees) is π/2 radians.

🎵 Note:

But What is PI?

Pi is defined as the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter.

Here are three different ways of representing this relationship mathematically:

π = C / d

C = π * d

C = 2 * π * r

A circle with a diameter of 1 will have circumference of length pi:

C = 2 * π * r

(If d = 1 then r = 0.5)

C = 2 * π * 0.5

C = (2 * 0.5) * π

C = π

Visualized, here’s a circle with a diameter of 1. Watch as its circumference unrolls to a length of π:

Visualized another way:

⏳ Wait For It:

Pi crops up throughout math and physics. We’ll soon see how it relates to trigonometry.

Resources

- 📚 Prehistoric Calculus: Discovering Pi @ Better Explained

- 📚 Calculating Pi in Various Ways a Visualization

- 📚 The Tau Manifesto by Michael Hartl

Why Radians

Measuring rotation in radians can simplify our thinking. Here’s an example from betterexplained.com:

Imagine a monster truck with wheels that have a 2 meter radius.

If we know how fast the wheels are turning, how do we calculate the speed of the truck?

Using Degrees

Let’s say the wheels are turning 1080 degrees per second:

- That’s

1080 / 360 = 3rotations per second. - Therefore the distance travelled per second will be three times the circumference of the wheels.

C = 2 * π * r = 2 * π * 2 = 4 * π- So the speed is

3 * C = 12 * πmeters per second. - Which is????

Using Radians

Next we’re told the truck is moving at a different speed with the wheels turning 5 radians per second:

- For each radian the distance travelled is one radius (2 meters).

- At 5 radians per second the truck travels 2 meters 5 times, or 10 meters per second.

Much easier to think about and no pesky π.

Resources

Processing Angles

p5.js has a number of helper functions and constants that will come in handy when working with angles:

- 📜

angleMode()- Switch between radians (default) and degrees. - 📜 p5.Vector’s

heading()- Returns the angle of a vector. - 📜

PI, TWO_PI, HALF_PI, QUARTER_PI, TAU- Handy constants for these irrational numbers. - 📜

radians()- Converts degrees to radians. - 📜

degrees()- Converts radians to degrees. - 📚

translate()&rotate()- Rotate the drawing canvas around a point.

Angular Motion

Let’s use translate() & rotate() to rotate rectangle using p5.js:

let angle = 0; // Angle of the spinner.

function draw() {

// Clear the canvas purple.

background(146, 83, 161);

// Draw rectangle rotated by current angle around canvas centre.

translate(width / 2, height / 2);

rotate(angle);

rect(0, 0, width * 0.8, height * 0.1);

// Increment the radian angle.

angle += 0.01;

}

Edit Code Using p5.js Web Editor

Angular Acceleration and Velocity

We can apply our knowledge of Newton’s laws from the previous module to modify the angular motion using velocity, with acceleration based on mouse position:

// Determine acceleration based on mouse position.

angularAcceleration = map(mouseX, 0, width, -0.01, 0.01);

// Forces 101: Acceleration changes velocity.

angularVelocity += angularAcceleration;

angularVelocity = constrain(angularVelocity, -0.2, 0.2);

// Forces 101: Velocity changes angular rotation.

angle += angularVelocity;

Hover your mouse over the canvas. Angular acceleration is determined by the mouse’s x position.

Edit Code Using p5.js Web Editor

Spin It!

We could also simplify the user interaction using only velocity to let the user click and spin the rectangle:

// Save the angle from the previous frame.

previousAngle = angle;

if (mouseIsPressed) {

// Have spinner rotate using the mouse's heading.

angle = createVector(mouseX - width / 2, mouseY - height / 2).heading();

// Base spinner velocity on distance rotated since previous frame.

// Bug here if angle crosses -PI and PI, where delta becomes a sum.

angularVelocity = angle - previousAngle;

} else {

// Apply the current velocity to the angle.

angle += angularVelocity;

// Simple linear friction.

angularVelocity *= 0.98;

}

Click, drag, and release to spin the rectangle:

Edit Code Using p5.js Web Editor

Noisy Rotation

Physical motion aside, knowledge of translation and rotation in p5.js can lead to some amazing results.

In this sketch by Gene Kogan our old friend Perlin Noise is used here to control the inner and outer rotations, translations, and square sizes.

Edit Code Using p5.js Web Editor

🎵 Note:

The code also makes clever use of nested rotation and translation using push and pop.

Trigonometry

In the Spin It! sketch we used the .heading() method to get an angle from vector, but how exactly was that done “under the hood”?

The secret lies in trigonometry, the branch of mathematics that studies relationships between side lengths and angles of triangles.

Trigonometry also reveals the hidden concepts that relate circles to triangles.

We can use trigonometry to:

- Determine the rotation of a vector.

- Find the angle between two given points. (Think simple AI steering and aiming.)

- Find the distance between two points. (Think simple collision detection.)

- Simulate physical systems that involve harmonic motion (waves, pendulums, springs).

⏳ Wait For It:

The heading() secret mentioned above will be revealed below.

The Right Triangle

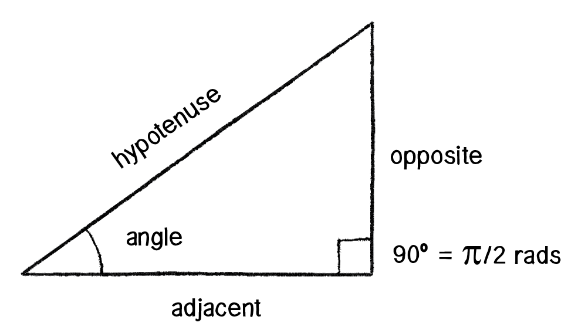

A triangle is a 2D shape that has three sides and three angles that add up to 180 degrees (π radians).

A right triangle (right-angled or orthogonal triangle) has one angle that is 90 degrees (π/2 radians). The other two angles always add up to 90 degrees but can be different sizes.

Which Side Are You On?

The hypotenuse is the longest side of a right triangle. It is always across from the right angle.

The other two sides are the legs, and are named in relation to one of the non-right angles.

Given one of the non-right angles, each leg will be either opposite that angle, or adjacent to it.

Resources

The above definitions were sources from:

SOH CAH TOA - Right Triangle Sides and Angles

Using the Pythagorean theorem (a² + b² = c²) we can determine the length of any side of a right triangle when given the other two sides.

The trigonometry functions sine, cosine, and tangent give us ways to determine the length of sides and angles of a right triangle.

- Sine:

sin = opposite / hypotenuse - Cosine:

cos = adjacent / hypotenuse - Tangent:

tan = opposite / adjacent

Some people remember these relationships using the catch phrase: SOH CAH TOA

Resources

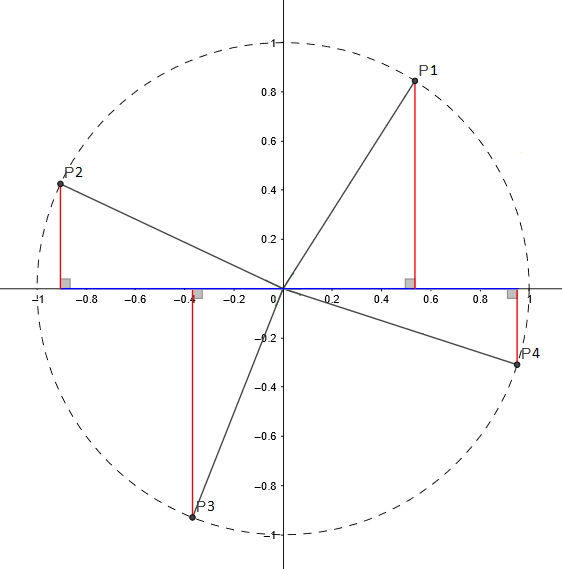

The Triangle and The Circle

Let’s return to the circle for a moment.

Any point along a circle’s circumference also describes a right triangle attached to the origin.

Each of those points can be described by either:

- An x and y coordinate.

- The angle within a right triangle. (Where the hypotenuse is the circle’s radius.)

Trig and The Circle

This means that trig can be used to relate circle points at specific angles to x and y coordinates!

When given a point at a specific angle along the circumference of a circle…

We can find the y coordinate using sin:

sin(angle) = opposite / hypotenuse

sin(angle) = y-coordinate / radius

y-coord = radius * sin(angle)

We can find the x coordinate using cos:

cos(angle) = adjacent / hypotenuse

cos(angle) = x-coordinate / radius

x-coord = radius * cos(angle)

Visualizing The Trigonometry of Circles and Right Triangles

As the angle around a circle increases, y moves in a wave between 0 to 1 to 0 to -1 to 0.

We call this motion a sine wave.

The x coordinates also move in a wave between 1 and -1 as the angle increases.

The change in x around a circle is a cosine wave.

Interact with angles and circle coordinates here.

Resources

- 📚 Intuitive Understanding of Sine Waves @ Better Explained - Sine as acceleration opposite to your current position; a continual pull back to centre. A must read!

- 📚 Sine and Cosine Explained Visually

Polar vs Cartesian Coordinates

We can now see that any point can be equally described by:

- An x and y coordinate.

- An angle around the origin paired with a distance (radius) from the origin.

The first (x and y) is called a Cartesian coordinate, the second (angle and radius) is called a Polar coordinate.

We can use trig to convert back and forth between Cartesian and Polar coordinates.

Polar and Cartesian Processing

Given a polar coordinate with a fixed radius and an angle tied to the mouse’s x position:

radius = 180;

angle = map(mouseX, 0, width, 0, TWO_PI);

We can draw the associated circle:

circle(0, 0, radius * 2);

The equivalent Cartesian point:

let x = radius * cos(angle);

let y = radius * sin(angle);

point(x, y);

And the underlying right triangle:

triangle(0, 0, x, 0, x, y);

Click the sketch below to reveal the associated cartesian point, then hold any key to change the radius.

Explore the Full Code Using p5.js Web Editor

Why Polar Coordinates?

There are situations where thinking in polar proves easier than working with Cartesian points.

Think about a cartoon explosion generator, where each frame of the explosion is a “spiky circle”.

We can define a polygon using beginShape() and endShape() with vertices (points) defined by a series of polar coordinates with random radius and an increasing angle.

let angleDelta = 0.1;

let minRadius = 100;

let maxRadius = 300;

translate(width / 2, height / 2);

beginShape();

for (let angle = 0; angle <= TWO_PI; angle += angleDelta) {

let radius = random(minRadius, maxRadius);

let x = radius * cos(angle);

let y = radius * sin(angle);

vertex(x, y);

}

endShape(CLOSE);

FLASH WARNING: Bottom slider controls the framerate. A high framerate could be an epilepsy danger!

Explore the Full Code Using p5.js Web Editor

From Vector to Heading

Remember when I promised to reveal the secret of the P5.Vector heading() method?

We used heading() to get the angle of a vector in the Spin It! demo. In our physical simulations we can also use it to have objects point in the direction of motion.

We previously handled the indication of direction in the Mouse Seeking Mover Sketch (lines 41 to 43 of mover.js shown below) using a copy of the velocity vector:

// Draw a "nose" on the mover indicating the direction of the velocity.

let noseLength = map(this.velocity.mag(), 0, this.speedLimit, 0, this.size);

let direction = this.velocity.copy().setMag(noseLength);

line(0, 0, direction.x, direction.y);

But what if our mover was an image sprite that we needed to rotate to the direction of movement?

The simplest solution would be to call heading() on the velocity to get rotation, but let’s see how we could accomplish this manually using trigonometry.

Sprite Mouse Seekers

Here’s an updated version of our mouse seeking mover sketch that uses image sprites.

Click for more space ships, then press any key to see a debug line representing their velocity vectors.

Explore the Full Code Using p5.js Web Editor

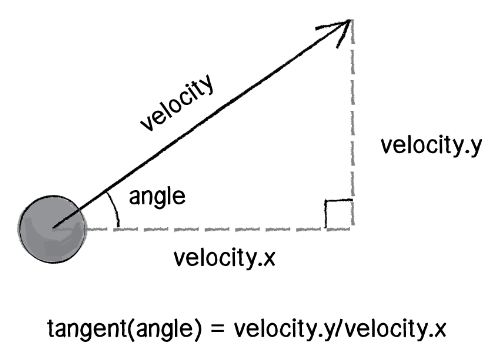

Rotating Towards Movement

Using trig to find the angle of our ship’s motion means constructing a right triangle using the x and y components of its velocity.

We know the angle’s Opposite and Adjacent sides, so it’s TOA or tangent to the rescue.

tan(angle) = opposite / adjacent

tan(angle) = velocity.y / velocity.x

To solve for the angle we need to do what’s called an inverse tangent (otherwise known as arctangent, arctan, or atan), which works like this:

tan(a) = b

a = arctan(b)

In our case b is the slope of the velocity, rise over run or y over x, so using the p5.js atan() function.

let angle = atan(this.velocity.y / this.velocity.x);

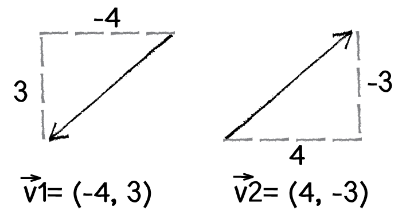

A Minor Issue

But there’s a problem!

Arctangent only provides half the picture.

Vectors of equal length but opposite direction are assigned equal angles when using arctangent.

Let’s look at the example to the right.

atan(3/-4) = atan(-0.75) = -0.6435011 radians

atan(-3/4) = atan(-0.75) = -0.6435011 radians

Luckily p5js (and many other programming environments) provide atan2() which includes extra logic to distinguish opposite vectors. With atan2() we pass the y and x values as separate arguments:

let angle = atan2(this.velocity.y, this.velocity.x);

Resources

- 📜

atan() - 📜

atan2() - 📚 Speeding up atan2f by 50x - Specific to the C language, but still fascinating.

Let’s Surf

Okay! That’s the baseline math behind circles, right triangles, and the trigonometric functions, but trig can do so much more for us!

Let’s look again at the motion of sine and cosine as we fed them angles from 0 to 2 π.

Sine moves smoothly starting at 0, up to 1, down to -1, and then back up to 0. Repeat.

Cosine moves smoothly starting at 1, down to -1, and then back up to 1. Repeat.

We can use these waves to smoothly bounce any variable between to values.

Like Day and Night

Here’s some basic harmonic motion in motion.

This sketch uses a sin wave to control the background color, along with the y position of the sun and moon.

// We'll feed this small frame by frame change into sin.

// Changing the divisor will speed up or slow down the transitions.

let tinyChange = frameCount / 100;

let dayBackground = color("skyBlue");

let nightBackground = color("black");

// Map the -1 to 1 swings of the changing sine output to the moon's

// verticle position on and off the screen.

let yPositionMoon = map(sin(tinyChange), -1, 1, 75, height * 3);

// Offset sin input by PI to place the sun and the moon on opposite "sides"

// of the wave. The moon peaks when the sun valleys, and vice versa.

let yPositionSun = map(sin(tinyChange + PI), -1, 1, 75, height * 4);

// Manually normalizing the sin wave between 0 and 1, instead of using map.

// Equivalent to: let lerpPosition = map(sin(tinyChange), -1, 1, 0, 1);

let lerpPosition = 0.5 * sin(tinyChange) + 0.5;

// Linear interpolation between the day and night sky.

let skyColor = lerpColor(nightBackground, dayBackground, lerpPosition);

Explore the Full Code Using p5.js Web Editor

Waves with Amplitude and Period

In the above sketch we fed values into sin() that changed by a tiny amount each frame. We also used the map() function to map the -1 to 1 output of sin() to different ranges.

Another way to work with the output of sin() is to think about the amplitude and period of the generated wave.

The amplitude controls the high and low points of the wave, while the period controls the speed of the oscillation.

let amplitude = 100;

let period = 120;

let waveform = amplitude * sin((TWO_PI * frameCount) / period);

Here the value of waveform will vary from 0 to 100 to 0 to -100 to 0. This wave will repeat every 120 frames.

If we preferred starting at 100 going down to -100 and back up to 100 we could use cosine instead:

let amplitude = 100;

let period = 120;

let waveform = amplitude * cos((TWO_PI * frameCount) / period);

Edit the Code Using p5.js Web Editor

🎵 Note:

Oscillation speed is sometimes measured in terms of frequency, which is 1 over the period.

Angular Velocity in 2D

Let’s take this knowledge and use it to simulate a collection balls swinging around on perfectly elastic strings. Click the canvas to respawn the oscillators.

Edit the Code Using p5.js Web Editor

In this sketch each ball has a fixed 2D velocity, but this velocity doesn’t feed directly into its position. Instead, the velocity is used to control two slowly increasing angles fed into sin(). Each oscillator also has a 2D amplitude which controls how far it will swing back and forth in the x and y directions.

Once per frame the oscillator’s position is updated like this:

this.angle.add(this.velocity);

this.position.x = this.amplitude.x * sin(this.angle.x);

this.position.y = this.amplitude.y * sin(this.angle.y);

Do the Worm

In this sketch we’ll simulate the undulation of a worm using a sine wave.

The y position of each circle is defined by a sine wave. Each circle is sampling the same wave but with a slight increase (“piecewise step”) of the input angle from the previous circle. The angle used to control the left-most circle is also increasing (“meta velocity”) with each frame.